I hope to have some exciting news to highlight this week regarding SpreadingScience and the work I am doing. If the outside world does not interfere.

Tag Archives: General

Tour de France as a community

by mikebaird

by mikebaird

Contador needs to let Schleck beat him tomorrow in order to win.

Contador may have to make abeyance to the peloton for what he did today. Otherwise, there could be some really dangerous times ahead for him. The peloton is not happy. I think he may purposefully give back the yellow jersey tomorrow to Schleck.

Contador, who is such a good time trialist that he can probably overcome a 90 second deficit in the last time trial later this week, broke a major peloton rule today. The yellow jersey, Andy Schleck, attacked on a steep hill and slipped a gear, forcing him to stop. I have watched the replays several times to see what happened next.

The ‘rules’ state that no one else attacks until the yellow jersey regains his bike. You do not take unfair advantage just so you can wear the yellow jersey. Another rider, Alexandre Vinokourov, had been sprinting with Schleck. He immediately slowed down. As expected.

Not Contador. From several meters behind Schleck, he attacked hard, passing the yellow jersey and continued on. By doing this he violated the rules and put himself into the yellow jersey at the end of the day. Schleck tried hard to come back but was not allowed to by Contador.

Interestingly, Vinokourov showed the honor and respect usually displayed by race leaders. He is on the same team as Contador and could have kept up with him. Having a teammate along with him would have helped Contador gain even more time.

Instead, Vinkourov finished in the same time as Schleck. He did not take advantage of the mechanical failure. He followed the ‘rules.’

When Contador put on the yellow jersey, I heard audible boos from the crowd, the first time I had ever heard such a thing. There was a lot of unhappiness all around.

Contador is only 8 seconds ahead of Schleck. He should be able to make up a lot of time in the time trial. Tomorrow, he could sit back and let Schleck pick up 30 seconds or so, putting things back to where they were. Schleck puts on the yellow jersey, things are back to normal, the peloton is happy and Contador comes out looking great, displaying the honor and leadership the peloton looks for.

And he can still win it all at the Time Trial.

Contador has shown himself capable of fixing things when he breaks a rule. He did this on an earlier stage when circumstances made him pass and beat a teammate, one who had been out in front for some time. A Tour leader does not need to win every stage to win the Tour and usually the other team members are allowed to win a stage to reward them. But Contador took that away from his own teammate, who was visibly unhappy at the result.

What happened the next stage? Contador and the other team members made sure that this unhappy teammate was rewarded. They made sure he won the next stage.

Interestingly, the unhappy teammate was Vinokourov, the same one who followed the rules today. Perhaps Contador will again fix things. That would be really amazing.

Now what is all of this about ‘rules’, unhappy pelotons, leadership and what not? Isn’t everyone out to win, everyman for themselves?

Not the Tour de France. In order to just survive without major injuries, the peloton has to operate as a community, protecting its members and allowing all sorts of unspoken rules to develop. Without this, there would be very few racers who would survive to the end. Every man for themselves would result in massive numbers of injuries, deaths and few racers surviving to Paris.

No one would enter a race that they would most likely not survive.

I have been following the Tour for over 30 years, before Armstrong, before Lemond, even before TV coverage in the US. Cycling is a perfect example of all that is great and all that is horrendous in sport. The riders have done everything they can to provide unfair advantages for themselves before the race – every drug in the world has been used.

Yet, during the race, when there would be all sorts of opportunities to take unfair advantage in order to win, we seldom see any. And when it does happen, the riders usually take some very direct action to demonstrate their unhappiness.

The peloton, once it really forms, creates a traveling community, an ad hoc social network, one that has its own rules and own enforcement in order to make sure no one breaks the rules of the community.

Any group of 200 or so people all focussed on a common goal will develop very similar characteristics. Add in tremendous personal dangers and you will often find a community that develops its own rules and viewpoints in order to adapt and survive. They can only survive if all the members of the community recognize the rules and characteristics that develop.

In the Tour, some characteristics that always seem to be there are ones of character, respect, phlegmatic outlook and honor. Lacking these, I do not believe the peloton could survive the 3 weeks of the Tour without complete disintegration. In order to make it through so many of grueling physical endeavors, the Tour and the peloton select for individuals that respond by developing these three traits.

These men race up to 100 km/hr in a physically draining sport that can produce horrendous bodily damage and even death. It would be very easy for unscrupulous riders to move themselves up in the peloton by knocking people over, etc. There are plenty of opportunities to do this over 3 weeks. Think of NASCAR over a three week period with races along shear cliffs.

They have to trust in the character of the other riders because even a short lapse in attention can wreck havoc with everyone.

They have to respect the abilities of others because their survival in the race could depend on those abilities.

They have to be able to keep strong emotions in check because real anger can result in violent injuries to others. Road rage produces a rider that simply will not make it through the entire Tour and represents a danger to others.

They have to honor those that are simply better because dishonor and disrespect open up pathways for really serious physical injury and complete destruction of the community formed in the Tour.

Riders that are unable to display these traits will be quickly displaced by the members of the community, if the peloton hopes to survive to Paris. When riding at high speeds right on the wheel of another rider, they have to know that nothing stupid will happen.

And lots of stupid things happen early on in every Tour, as the community is forming. This is when all the crashes happen, as the community begins to figure out who will help it survive. This is always the most dangerous time.

But always things rapidly change. The peloton adapts, developing the characteristics necessary to make it to Paris. There are very few Tours where there have been major crashes involving large parts of the peloton late in the race. The little community has adapted and can just race at high speeds.

The peloton knows which riders to stay away from when in a dangerous situation (often these members are relegated to the back or simply do not finish the Tour) , which ones can be counted on to show courage and honor, to protect themselves and others. Inevitably, the entire group recognizes those who make it safe to really compete and those who can be dangerous.

This Tour has been a little different in some ways. In particular, it had the nasty cobblestone section early, which would be dangerous under the best of circumstances. Happening before the peloton had really gotten together, it permitted lots of dangerous actions to occur, which had major consequences for the leaders. If the cobblestones had happened later in the race, I do not expect quite as much havoc to have occurred.

The peloton was not happy. It demonstrated its displease with the outsiders – the Tour organizers – the next day by purposefully not racing. They organized themselves to simply cross the line together, with no winners. Several of the sprinters were visibly upset that they could not sprint at the end but they knew better – do not go against the wishes of the peloton if you want to be allowed to be a member.

Strong social mores had already developed, controlling the behaviors of all the members of this community.

In a later race, we had a racer – Renshaw – do something really dangerous in order to help his teammate win. In a full sprint, where 10-20 racers are moving at full speed to the finish, he looked back, slowed down and looked to purposefully move over to drive a competitor against the wall. At the 50-60 km/hr these guys are going, this was an incredibly dangerous thing to do.

Almost all the sprinters were rightly upset at this incredibly dangerous move. They have to trust that the other sprinters will not be trying to kill them. He endangered all of them with his unfair behavior. There had to be some response to this blatant attempt to destroy the collegiality of the group.

Renshaw was disqualified from the race, totally removed from the Tour community. His flouting of the ‘rules’ of the peloton resulted in his removal. Possibly for his own good. As we saw earlier, the peloton can take things into its own hands if need be.

Now, one the the other ‘rules’ of the peloton is that you do not take advantage of the man in yellow if he suffers a mechanical failure. There is honor and respect that goes to the main in yellow. Taking an unfair advantage is actually dangerous for the peloton. It creates doubt in the peloton for the character of other racers. ‘If they will do this to win, what else will they do?’

When individuals in the peloton begin to doubt the leaders, the possible disintegration of the community emerges. And if that happens, there can be some serious injuries ahead.

I think that in order to maintain the community of the peloton, Contador must do something. If he fails to recognize his breaking of the rule, even if it was unintentional, he risks a disintegration of the peloton and a really dangerous situation. Every man for themselves is a recipe for real disaster for the racers.

There are all sorts of ways the peloton can show its displeasure, in ways quite harmful for Contador and his team.

Contador can easily appease the peloton without doing any real damage for his chances. SImply let Schleck win tomorrow by more than 8 seconds. He can put Schleck back in the yellow, recognizing the tremendous work the other racer has done, without really hurting his chances for a win.

Otherwise, he really risks a lot. Not just this year but in future Tours. He may never really be trusted by the peloton ever again.

Who am I?

I figure that I may be getting some traffic from the Huffington Post article so an introduction.

I’ve been working in the field of biotechnology since the early 80s, spending 16 years as a researcher at Immunex, the premier biotech in the Seattle area until it was bought by Amgen. It was an incredible crucible of top-notch researchers working with little money to find cures for important diseases. There were, I believe, less than 50 employees when I started and several thousand when I left. So I had first hand knowledge of many of the needs of a small biotech as it grew. I was a small part in the development of a biologic that changed people’s lives – ENBREL.

I left Immunex when Amgen finalized the merger and spent some time thinking about what to do next. Luckily Immunex stock options, which were given to all Immunex employees when I started, provided some economic buffer. I worked with the Washington Biotechnology and Biomedical Association on several projects and helped form a philanthropic organization called the Sustainable Path Foundation, where I am still a Board member.

I started a blog called A Man With a PhD, something I continue to this day, as well as a science-based blog called Living Code for Corante, that Forbes picked as the 3rd best Medical blog in 2003.

In 2004, I became the third employee of a startup biotechnology company called Etubics. As VP in charge of Research, I did everything from ordering lab equipment, growing cells, negotiating contracts and having to fly cross country to talk with suppliers. All while trying to raise money so we could have a hope of producing the vaccines that I believe can change the world.

So I got to see firsthand and at the highest levels, what it takes to start and run a company. I left last year as the company was entering a new phase, where clinical development and manufacturing were at the forefront and research was on the back burner. Not only were these areas I did not have a lot of expertise or interest, but I also was pretty well burned out. The stress of a small company is enormous, particularly in an industry where it takes over 15 years for a therapeutic to get from the research lab to the patient.

I left to pursue one of my real passions – how to understand why Immunex was such a powerhouse of research, why it is was one of the few biotech companies started in the 80s to produce a blockbuster drugs, along with several other good drugs, and whether this could be replicated.

That is what SpreadingScience is about – how to create organizations that are resilient to change, that can adapt in ways that increase the successful outcomes need. You can read some of the material or follow my blog to get an idea of how I am accomplishing this.

Disruptive technology seldom is accurately described during its disruptive period

Apple’s “history of lousy first reviews”

[Via Edible Apple]

From the original Mac to the iMac to the iPod and even the iPhone, early reviews of revolutionary products tend to evoke a lot of negative reactions. The Week takes us back in time and examines what reviewers have historically thought about Apple’s latest and greatest creations.

[More]

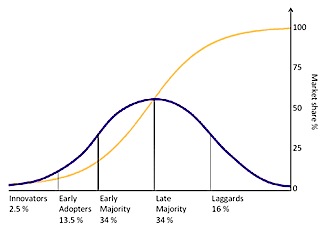

The problem with so many new, disruptive technologies is that most people do not understand them. Let me pull back a little bit to discuss how innovations are accepted by a community, using the model proposed by Everett Rogers.

The majority of people do not change, do not take up new things, very rapidly. They like to stick with what they know.

A small group do accept new things very fast. These so called innovators are the ones that almost always make up the tech community.

Read any tech blog and you’ll see all sorts of stuff regarding the coolest new toys. They know in detail just why a new product is worthy, usually because it is the best, fastest, newest.

Now, to get new technology out of the hands of the innovators and into the majority requires the work of early adopters. These act as filters, helping move innovations that can make a real difference to the majority, out of the hungry hands of the innovators.

These people are pretty special because, for all sorts of reasons, the majority just will not listen to the innovators. They are too disruptive. They might listen to the early adopters because this group seems to know how to mediate between the two groups that often fail to communicate at all.

Now, the people who write about high tech are usually of two types (and this holds for any writing about rapidly changing technologies). They either write for the innovators, providing insights into the newest. Or they write for the majority, providing a comfortable view of how the rapid churn of the new can be ‘controlled’.

To really be successful, a technology needs to move out from the innovators to the majority. But who will write about this? Those that cater to the innovators will not because the technology that is usually being moved is ‘old hat.’ That is who their audience is.These writers always tell us how there are faster things with more memory that can do the same thing. “My hand-built PC is able to do three times as much for half the price.”

And what about those who cater to the majority? Well, they are usually skeptical of anything new. That is who their audience is. So this disruptive technology is often viewed in the same way as any other – something to be feared and watched carefully. “This computer is really slow and will never replace the speed of a mainframe.”

If you look at the criticisms of Apple products over the years, especially the ones that have been shown by history to be flat out wrong, you see they fall into one of these two bins.

What Apple has done, more than most other companies, is act first to move technologies and ideas out of the hands of the innovators, into the land of the majority. This does not mean they have to be the most innovative or always have the best ideas. What they have been successful at is becoming the premier company of transitioning technology. They filter out the technology, finding the best ones to move out to the majority.

Few companies are able to do this even once. The fact that Apple has done this in multiple product categories is amazing.

And, just as early adopters are usually the opinion and thought leaders of a community, so Apple is watched to see what will become the new paradigm for the majority. This explains why keynotes given by Steve Jobs can bring down the internet.

Most pundits and commenters on Apple, and on any disruptive technology, will continue to get it wrong. Few people are able to effectively, and accurately, discuss the views of the early adopter segment. I think that might be because to do that requires someone who can simultaneously understand both the views of the innovator cohort and the majority. These people seem to be pretty rare and can probably find a more lucrative livelihood than writing for a magazine. Perhaps working for Apple.

Innovation on the cheap

by jordigraells>

by jordigraells>

Why Great Innovators Spend Less Than Good Ones

[Via HarvardBusiness.org]

A story last week about the Obama administration committing more than $3 billion to smart grid initiatives caught my eye. It wasn’t really an unusual story. It seems like every day features a slew of stories where leaders commit billions to new geographies, technologies, or acquisitions to demonstrate how serious they are about innovation and growth.

Here’s the thing — these kinds of commitments paradoxically can make it harder for organizations to achieve their aim. In other words, the very act of making a serious financial commitment to solve a problem can make it harder to solve the problem.

Why can large commitments hamstring innovation?

First, they lead people to chase the known rather than the unknown. After all, if you are going to spend a large chunk of change, you better be sure it is going to be going after a large market. Otherwise it is next to impossible to justify the investment. But most growth comes from creating what doesn’t exist, not getting a piece of what already does. It’s no better to rely on projections for tomorrow’s growth markets, because they are notoriously flawed.

Big commitments also lead people to frame problems in technological terms. Innovators spend resources on path-breaking technologies that hold the tantalizing promise of transformation. But as my colleagues Mark Johnson and Josh Suskewicz have shown, the true path to transformation almost always comes from developing a distinct business model.

Finally, large investments lead innovators to shut off “emergent signals.” When you spend a lot, you lock in fixed assets that make it hard to dramatically shift strategy. What, for example, could Motorola do after it invested billions to launch dozens of satellites to support its Iridium service only to learn there just wasn’t a market for it? Painfully little. Early commitments predetermined the venture’s path, and when it turned out the first strategy was wrong — as it almost always is — the big commitment acted as an anchor that inhibited iteration.

[More]

One problem of too much money is that bad ideas get funding also. In fact, there are often many more incremental plans than revolutionary ones. They soak up a lot of time and money.

Plus they create the “We have to spend this money” rather than “Where are we going to get the money to spend?”

Innovations often result in things that save money. But they are often riskier to start with. So how to recognize them and get them the money they need, but not too much?

Encouraging people to work on ‘back burner’ projects in order to demonstrate the usefulness of the approach is one way. Careful vetting can help determine whether it can be moved to the front burner or not.

Part of any innovator’s dilemma is balancing the innovative spirit with sufficient funding to nurture that spirit, without overwhelming the innovator with the debit of too much cash.