Apple’s “history of lousy first reviews”

[Via Edible Apple]

From the original Mac to the iMac to the iPod and even the iPhone, early reviews of revolutionary products tend to evoke a lot of negative reactions. The Week takes us back in time and examines what reviewers have historically thought about Apple’s latest and greatest creations.

[More]

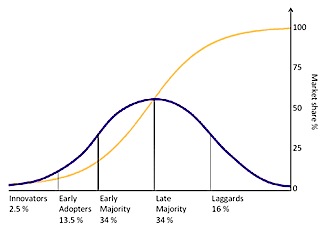

The problem with so many new, disruptive technologies is that most people do not understand them. Let me pull back a little bit to discuss how innovations are accepted by a community, using the model proposed by Everett Rogers.

The majority of people do not change, do not take up new things, very rapidly. They like to stick with what they know.

A small group do accept new things very fast. These so called innovators are the ones that almost always make up the tech community.

Read any tech blog and you’ll see all sorts of stuff regarding the coolest new toys. They know in detail just why a new product is worthy, usually because it is the best, fastest, newest.

Now, to get new technology out of the hands of the innovators and into the majority requires the work of early adopters. These act as filters, helping move innovations that can make a real difference to the majority, out of the hungry hands of the innovators.

These people are pretty special because, for all sorts of reasons, the majority just will not listen to the innovators. They are too disruptive. They might listen to the early adopters because this group seems to know how to mediate between the two groups that often fail to communicate at all.

Now, the people who write about high tech are usually of two types (and this holds for any writing about rapidly changing technologies). They either write for the innovators, providing insights into the newest. Or they write for the majority, providing a comfortable view of how the rapid churn of the new can be ‘controlled’.

To really be successful, a technology needs to move out from the innovators to the majority. But who will write about this? Those that cater to the innovators will not because the technology that is usually being moved is ‘old hat.’ That is who their audience is.These writers always tell us how there are faster things with more memory that can do the same thing. “My hand-built PC is able to do three times as much for half the price.”

And what about those who cater to the majority? Well, they are usually skeptical of anything new. That is who their audience is. So this disruptive technology is often viewed in the same way as any other – something to be feared and watched carefully. “This computer is really slow and will never replace the speed of a mainframe.”

If you look at the criticisms of Apple products over the years, especially the ones that have been shown by history to be flat out wrong, you see they fall into one of these two bins.

What Apple has done, more than most other companies, is act first to move technologies and ideas out of the hands of the innovators, into the land of the majority. This does not mean they have to be the most innovative or always have the best ideas. What they have been successful at is becoming the premier company of transitioning technology. They filter out the technology, finding the best ones to move out to the majority.

Few companies are able to do this even once. The fact that Apple has done this in multiple product categories is amazing.

And, just as early adopters are usually the opinion and thought leaders of a community, so Apple is watched to see what will become the new paradigm for the majority. This explains why keynotes given by Steve Jobs can bring down the internet.

Most pundits and commenters on Apple, and on any disruptive technology, will continue to get it wrong. Few people are able to effectively, and accurately, discuss the views of the early adopter segment. I think that might be because to do that requires someone who can simultaneously understand both the views of the innovator cohort and the majority. These people seem to be pretty rare and can probably find a more lucrative livelihood than writing for a magazine. Perhaps working for Apple.