Four Ways of Looking at Twitter

[Via HarvardBusiness.org]

Data visualization is cool. It’s also becoming ever more useful, as the vibrant online community of data visualizers (programmers, designers, artists, and statisticians — sometimes all in one person) grows and the tools to execute their visions improve.

Jeff Clark is part of this community. He, like many data visualization enthusiasts, fell into it after being inspired by pioneer Martin Wattenberg‘s landmark treemap that visualized the stock market.

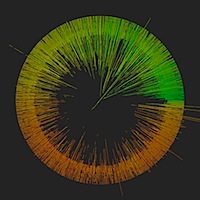

Clark’s latest work shows much promise. He’s built four engines that visualize that giant pile of data known as Twitter. All four basically search words used in tweets, then look for relationships to other words or to other Tweeters. They function in almost real time.

“Twitter is an obvious data source for lots of text information,” says Clark. “It’s actually proven to be a great playground for testing out data visualization ideas.” Clark readily admits not all the visualizations are the product of his design genius. It’s his programming skills that allow him to build engines that drive the visualizations. “I spend a fair amount of time looking at what’s out there. I’ll take what someone did visually and use a different data source. Twitter Spectrum was based on things people search for on Google. Chris Harrison did interesting work that looks really great and I thought, I can do something like that that’s based on live data. So I brought it to Twitter.”

His tools are definitely early stages, but even now, it’s easy to imagine where they could be taken.

Take TwitterVenn. You enter three search terms and the app returns a venn diagram showing frequency of use of each term and frequency of overlap of the terms in a single tweet. As a bonus, it shows a small word map of the most common terms related to each search term; tweets per day for each term by itself and each combination of terms; and a recent tweet. I entered “apple, google, microsoft.” Here’s what a got:

Right away I see Apple tweets are dominating, not surprisingly. But notice the high frequency of unexpected words like “win” “free” and “capacitive” used with the term “apple.” That suggests marketing (spam?) of apple products via Twitter, i.e. “Win a free iPad…”.

I was shocked at the relative infrequency of “google” tweets. In fact there were on average more tweets that included both “microsoft” and “google” than ones that just mentioned “google.”

[More]

Social media sites provide a way to not only map human networks but also to get a good idea of what the conversations are about. Here we can see not only how many tweets are discussing apple, microsoft and goggle but the combinations of each.

Now, the really interesting question is how ti really get at the data, how to examine it in order to discover really amazing things. This post examines ways to visually present the data.

Visuals – those will be some of the key revolutionary approaches that allow us to take complex data and put it into terms we can understand. These are some nice begining points.